Law enforcement has to be part of the prevention workforce. The question is: how and where?

Law enforcement has to be part of the prevention workforce. The question is: how and where?

Introduction

The role of Law Enforcement Officers (LEO) in prevention is an important and controversial question. In Europe, currently, only few people do naturally see LEO as part of the prevention workforce. And if they do consider LEO as preventionists, they tend to think that the role of LEO in substance use or crime prevention is similar to what the conventional substance use prevention workforce has been doing to date: that they should educate kids about the legal and health consequences of substance use, that they should go into schools and deliver prevention programmes, ‘drug education’ or simply warning sessions. These practices seem to be based on a widespread misconception about prevention, which is: “giving teenagers accurate and objective information about the harms done by drugs”. In reality, though, the currently available research shows that there is hardly any evidence that only lecturing about psychoactive substances, showing drug samples to kids, or talking about rules and the law leads to changes in behaviour. In principle it is certainly a good thing and even a right for people to receive accurate and reliable information about matters that affect their lives: for travelling safely from A to B or for choosing a fridge. Yet, information provision and hence knowledge about risks or harms have so little influence on impulse-driven behaviours such as substance use, eating, or violence that the verdict of the prevention sciences is that information provision alone has no effects. It can even make things worse if it suggests, particularly to young people, that a given behaviour is frequent and normal. These so-called normative beliefs increase young people’s interest and engagement in such behaviours.

Information provision alone doesn’t really improve impulse-driven behaviours such as substance use, eating, violence or sedentarism

Therefore, the entire group of behavioural change techniques (BCTs), which we call informational (e.g., persuading, warning, educating, modelling), should be used with the greatest caution and refrainment because its evidence for actually making a positive change in people’s behaviour is wafer-thin. Despite this, it is a widespread and frequent practice to provide only knowledge about harms or risks to young people. Therefore, we should pay a lot of attention to improving the training of those delivering these approaches so that they may combine such purely informational activities with effective behavioural change strategies or change their intervention focus as a whole. What works well, however, is to provide information about behavioural norms, i.e., correcting normative fallacies: the beliefs that most relevant others are displaying a given behaviour and/or find it acceptable, or if information exposes industry tactics and narratives (e.g., telling youngsters how to deal with fake news). This, however, requires adequate and continued training of the workforce regarding the state of the art of prevention techniques.

What works well, though, is to correct normative fallacies: the belief that most relevant others are displaying a given behaviour or find it acceptable

We do not know whether the uniforms of LEO and their role in society really increase their credibility and authority for school-aged youth. In official prevention discourses in Europe such as strategy documents, it is nowadays less frequent to advocate for sending LEO into classrooms, but it is still a prevalent practice. Outside of Europe, however, it seems so relevant that UNODC[1] is launching a dedicated publication on improving the effectiveness and role of LEO in school-based prevention by explaining the principles of prevention science and the features of effective interventions for schools.Sometimes, but mostly outside of Europe, LEO deliver manualised prevention programmes in classrooms as a means to offer more than just risk information about psychoactive substances to kids. Yet, take the example of the most famous and most commonly used manualised LEO-delivered programme in the US and other countries of the Western Hemisphere: the evidence for that package in good evaluations in the US and Brazil overwhelmingly ranges between zero and negative, with no reliable long-term effects on adolescent substance use. While the detailed mechanisms of failure are unclear, it might be due to its delivery by uniformed police officers, since updating its active ingredients with more evidence-based contents did also not improve the results.

LEO doing prevention should avoid going into schools without specific training. Particularly not with:

- Drug samples

- Warning information alone

- Scary images or stories

- Sniffer dogs

Successful prevention activities have a developmental focus in their active ingredients. Prevention experts call interventions developmental if they equip children and adolescents with the necessary behavioural, social and personal skills for achieving their developmental goals while they grow into adulthood. The corresponding Life-skills-, Social-Emotional-Learning (SEL)- and Social-Influence-Programmes have a positive level of evidence in registries of effective interventions such as Xchange[2]. Yet, if LEO implement them, there is still no evidence of positive effects even if LEO are often well-trained and might be more motivated than teachers when they deliver interventions. Therefore, there is no good case in favour of sending LEO into classrooms to interact with young people. This doesn’t seem to be beneficial even when using developmental approaches, let alone when using informational ones.

Advocates for sending LEO in schools still argue that this improves the image of LEO in communities. Yet, this has not been documented to be an effective mean of preventing substance use, neither in school nor at the community level.

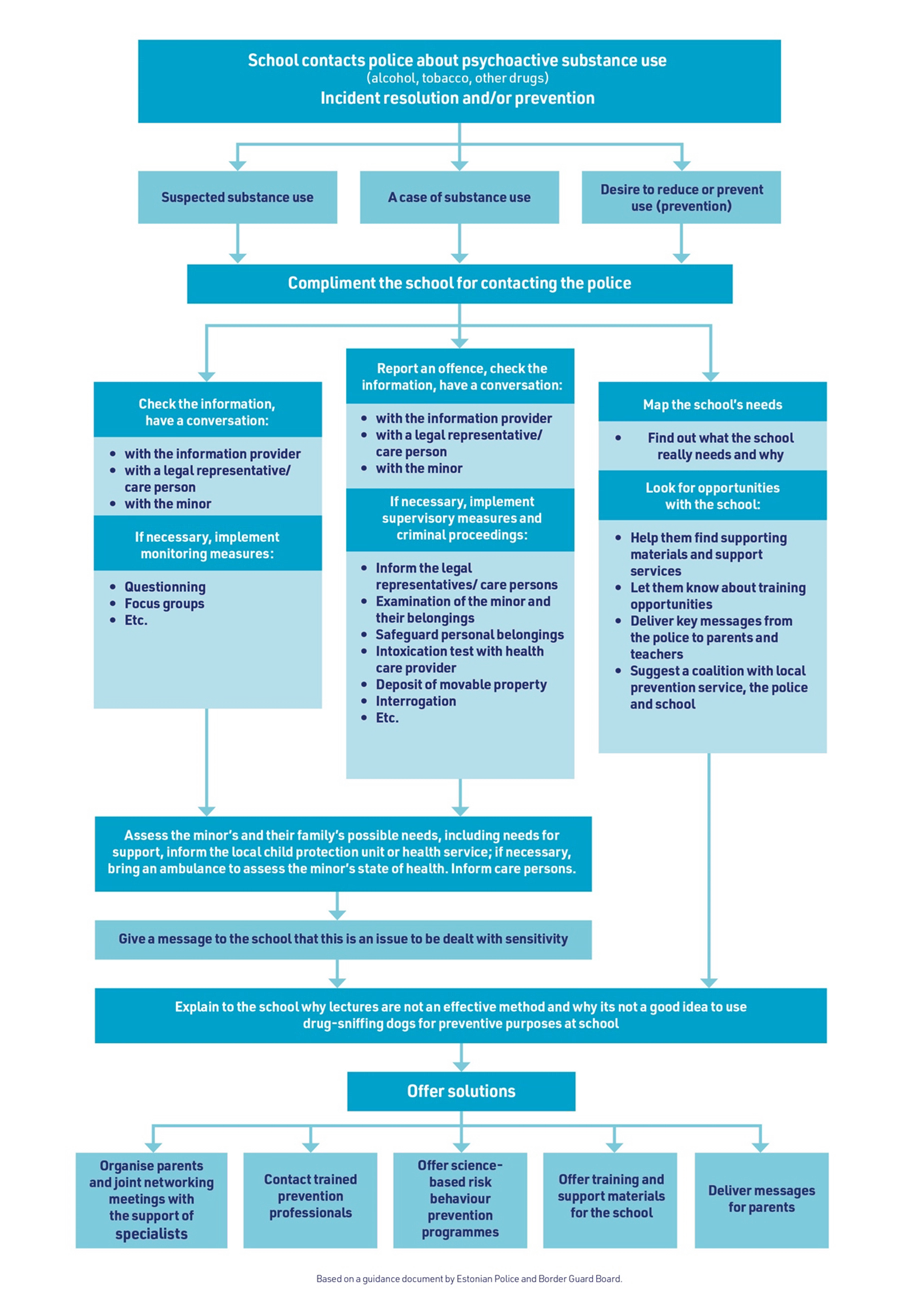

Frequent and positive interactions with LEO in real and daily life would be more effective in improving trust and relationship between youth and LEO than one-off arranged events in the class-room. Most people wouldn’t find this same argument appealing if it was rephrased, in analogy, as “even though the industries deliver ineffective interventions in schools, these activities do at least improve the image of commercial actors among young people”. The reality in many countries is, however, that schools themselves are calling LEO to come to schools, either because there is a shortage in the conventional prevention workforce, or because some schools want a stronger message than those of the (sometimes inadequately trained) prevention workers, who they might perceive as being too soft or apologetic on cannabis or party drugs. It is difficult for law enforcement agencies to refuse such requests. LEO can here act as a gatekeeper for prevention specialists and propose instead modern interventions together with other prevention agents. In the annex, you will find an example of how Estonian police deals with demands from schools.

Law enforcement has its own professional focus. Acknowledging this focus helps to define and clarify their role in prevention

The conventional prevention workforce consists of a very diverse range of professionals mostly from social sciences such as psychologists, sociologists, criminologists, educators, social workers etc. Each of these professions has their own professional culture with different working principles, core tasks and goals. Let us, for example, consider conventional prevention workers with a qualification in social work and compare their work principles with those of LEO. One of the core tasks of social workers with a prevention remit is to enhance wellbeing of individuals and groups, while one of LEO’s core tasks is to maintain order in public space and strive for a safe society. The law is LEO’s framework to address their target group, while for social workers it might be health or social inclusion. So, LEO have an important role in preventing crime (as one of their professional aims) and might set up extra preventive actions in the scope of – for example – problem-oriented policing and situational strategies (e.g., improving public spaces to prevent crime and nuisance). Such strategies have proven effects also on substance use.

Responsible prevention experts refuse invites by schools to give classroom talks about drugs. So should LEO. Suggest effective and sustained interventions instead that reflect your professional focus

LEO’s role is culturally-sensitive and it might have different aspects depending on each country’s prevention culture. Particularly outside Europe, LEOs may be the only workforce involved in substance use prevention, because there is no conventional prevention workforce as we know it in Europe. Differences are big also across European countries, and not everywhere LEO’s role is limited to upholding the law. Estonia and Belgium for example have “Community police” – police workers who cater for young people (e.g., who have committed offences, used substances, etc) and families –, and in other Northern European countries the police coordinates neighbourhood watch schemes sometimes involving young people. It seems to be typical of Europe’s diversity that LEO have a different involvement in prevention settings, based on each country’s culture. Being aware of the professional culture of law enforcement in each culture gives us a clearer view on their role in prevention and defines how they should be part of the prevention workforce. Also, different professions working together in similar settings will gain more knowledge about each other’s work, their roles and finalities: bridges can be built and synergies increased.

LEO in particular will then easier understand the ‘how’ and ‘where’ to intervene in the prevention of harmful behaviours.

So why are LEO so important? The answer lies in creating safer environments

The role of LEO in prevention is of utmost and crucial importance for a modern overarching conception of prevention that includes environmental prevention (called ‘situational prevention’ in the crime prevention field), which is the third group of the behavioural change techniques mentioned above. They enable changes to the configuration of incentives, norms, opportunities and triggers in human physical, economic and regulatory environments. This kind of interventions has a convincing strength of evidence, but is much less known and used. While the two above-mentioned informational and developmental prevention functions aim to make the individual more resilient, capable and competent (called i-frame), the environmental prevention function aims to re-design environments and systems (s-frame) so that behaviour change can occur with ease but with less agency (i.e., less use of behavioural and cognitive resources for steering behaviour).

Community-based and environmental prevention only do well with the engagement of LEO, particularly in nightlife

Many prevention professionals know the examples (e.g., upholding youth protection laws), know that they are effective, yet they often do not perceive them as “prevention” but as regulation or restrictions. Some professionals shun environmental interventions because they reject any regulatory take on prevention. In these examples, the importance of LEO for their proper implementation is self-evident: applying and enforcing legislation on under-age drinking or purchases, on drinking and driving, for supporting local policies related to smoking at work or school yards; monitoring advertising restrictions, reinforcing opening hours, or access limits and curfew hours for the underaged.

LEO can also monitor physical aspects of night and social life, such as the illumination of streets, signs of urban decay, the activity of dealers or (alcohol) sales outlets close to schools, the spatial configuration and crowd management of establishments and collaborate with commercial and public actors for improving these aspects. So, where conventional prevention workers target individuals, often in the school context, LEO are better placed to target people’s contextual, environmental factors, as shown in the following examples.

LEO and nightlife safety

The main aspects related to problems with substances and violence in nightlife are environmental factors: for example, dirtiness, lack of comfort, boredom, lack of ventilation, noise or very loud music, crowdedness, predominance of male patrons, many people under the influence of substances, untrained staff, a permissive ambience, “happy hours” and other drinking promotions. This brings many opportunities for LEO to make a difference, by regular visits to high-risk nightlife venues, to guarantee compliance with safety and serving rules, by carrying out age verification checks to reduce the access or serving to underage youth, and by enforcing responsible serving so that already-intoxicated people are not further harmed. An important point is that positive effects diminish if such LEO actions are not happening on a regular basis and/or linked to real deterrents for commercial actors, such as licence removal. Positive effects increase if LEO focus on targeted policing of hot spots in nightlife.

One of the best examples is the STAD[3] project in Sweden, in which LEO, the entertainment sector and conventional prevention workers cooperate and have achieved consistent positive outcomes on vandalism and substance use. Other promising examples for these principles have been documented in England & Wales, where interagency cooperation is mandatory, such as Citysafe in Liverpool or Tackling Alcohol-related Street Crime (TASC) in Cardiff, both of which were associated with significant drops in cases of violence.

Relatively simple regulatory strategies at municipal levels in England and the Netherlands, with proper LEO involvement can have large effects: there were clear declines in violent crimes, sexual crimes, public order offences, and hospital admissions. An important driver for successful implementation was to frame the challenges to be addressed as public nuisance issues, rather than health issues. Therefore, coalitions between both prevention workforces (LEO and conventional prevention workers), the nightlife businesses and local administrations are crucial for new forms of environmental prevention at local level.

LEO in communities and school yards

There are many positive experiences and evidences where LEO can make essential contributions to the prevention of problem behaviour where it matters most to people: in their own neighbourhoods and communities … and the surroundings of schools. A basic thing to do would be to enforce existing youth curfew hours, because it is a basic principle of youth protection to reduce the contact of minors with nightlife environments that get even riskier as the night progresses.

Another essential role of LEO is the control of alcohol sales to minors and enforcing legislation about substance use in public view.

From an environmental prevention perspective, it makes more sense for LEO to be present in school surroundings or in school yards in order to reduce the possibilities for violence and drug-dealing to occur. There is obviously a strong case for proximity policing and for providing a better feeling of safety and engagement with police. Some countries have set up youth-driven neighbourhood watch schemes (Lithuania) that support LEO work.Well-trained LEO can also have a key role in environmental scans where they can help to identify hot spots for problems and unethical industry activities (such as drinking promotions, flat-rates or serving to the underaged), propose physical or regulatory changes, or contribute to setting up safe and clean playing and leisure areas, and leisure time opportunities.

Figure: collaboration between school staff and LEO in the case of substance use prevention and/or incident resolution

How to make the necessary changes in prevention systems?

Providing tools, information and evidence about more meaningful and effective prevention strategies is unlikely to achieve changes, if critical parameters of a prevention system[4] are not touched upon. While there is general awareness that evidence-based interventions need to be available and ready for use, two parameters are far less addressed: the paramount role of the prevention workforce (including both decision-, opinion- and policy makers (DOPs) as well as frontline practitioners), and of the inter-sectorial cooperation.

While the training of DOPs is already being implemented as a result of previous EU-Projects, the currently ongoing EU-Project “Politeia” (2022-2023) complements these achievements seamlessly by covering the missing piece of training the frontline staff for prevention: teachers, social workers, prevention workers, and, importantly, LEO. Precisely, the cooperation between the sectors of society that should but rarely do work together in prevention, (social, health and law enforcement) is the key objective of this project. LEO and conventional prevention staff need to realise how much they can share, complement and support each other, if an innovative and broad view on prevention is applied and adopted by all players. Therefore, Politeia proposes blended (practical, e-learning and face-to-face) and cooperative forms of training and learning, with contents that are more relevant to frontline prevention workers (less on mass media or advocacy, as compared with the training of DOPs), and the possibility to choose elective modules (e.g., schools or nightlife).

Besides training, there are some basic conditions of collaboration between the conventional prevention workforce and LEOs, considering their different organisational culture (as described above). Both professions should understand each other’s professional role in society. They should gain knowledge about each other’s profession, respect each other in their different focus of work and accept that. Particularly because crime/violence prevention and substance use prevention can go hand in hand, they should be able to go into dialogue with one another and have the possibility to prevent and solve possible conflicts. A good coordination of their work is of big importance, together with sharing the same goals and beliefs (despite their difference in professional focus) to work towards, for example, a safe and healthy nightlife. When LEO and the conventional prevention workforce collaborate as prevention workforce in a comprehensive understanding, they should work on a local level, focusing on local situations and needs. Although individual relationships can mean a lot in those local settings, structures and procedures should be embedded.

In summary: LEO is crucial for better prevention if we get the right angle.

We need to frame the prevention of substance use problems and of violence as an issue of safer and nurturing environments where young people and adults have less opportunities for harmful behaviours and more incentives and opportunities for enriching activities.

In adolescence, many of the risk factors for substance use overlap with those for violence; it is therefore important to posit crime-prevention as congruent with substance use prevention: if done well, it can tackle both areas of concern. This naturally establishes a genuine and crucial role for LEO in such a comprehensive concept of prevention of problem behaviour.

Therefore, LEO have important roles in community-based prevention and environmental (situational) prevention, particularly in nightlife. The main conundrum to be solved is how new forms of professional working and attitudes can be promoted among professionals from different sectors. We suggest that one way forward is shared learning and sharing of implementation experiences with prevention professionals from other sectors.

When LEOs and the conventional prevention workforce collaborate in a community, they should respect each other’s work principles, knowing that their professional focus of intervention is different. Dialogues between the different professions are a first important step to realise a fruitful partnership.

LEO do have a great role in prevention because they can increase its effectiveness with their angle on environmental (situational) prevention in creating safer environments, so that the natural proneness of young people to experimenting with risks becomes less harmful.

Both LEO and conventional prevention workers need the right tools for effective behavioural change, on top of motivation and good intentions. Only then they can overcome the typical flaws of conventional prevention: its excessive or sole dependence on informational approaches and its overreliance on individual decision-making.

If LEO and the conventional prevention workforce train together, they can bring enriching and complementary angles, viewpoints and experiences to each other. The explicit aim of the Politeia project is therefore to get community stakeholders such as LEO, youth workers, local officials, teachers, and others to work together and by these means to improve the impact of local prevention strategies. We are convinced that Politeia can plant a seed for a fruitful, effective role for LEO in contributing to healthy and safe local communities with a good preventive governance, in reference to Plato’s dialogue Politeia.

Want to dig deeper into the science of prevention? The EMCDDA organises on regular basis online and face-to-face trainings in the ‘European Prevention Curriculum’ (EUPC). The aim of EUPC is to implement a standardised prevention training curriculum in Europe and improve the overall effectiveness of prevention. For more information, check the following link: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/best-practice/european-prevention-curriculum-eupc_en

Acknowledgements

The first version of this position paper was written by members of the Advisory Board of the Politeia Project, which includes representatives from EMCDDA, EUCPN, UNODC, and APSIntl. The EUSPR Board of Directors revised, edited and endorsed it as an EUSPR position paper.

- All position papers of the EUSPR are independent scientific statements about the available evidence on a particular theme, written by selected experts among its members, endorsed by the EUSPR board.

- The EUSPR is a non-profit organization committed to prevention science and, as such, does not engage with any type of commercial activities.

- EUSPR position papers address a broader public and therefore use plain language avoiding scientific jargon. For this reason, we do not add the references to the scientific articles and reviews of evidence on which we have based our statements.

- Readers with interest in the principles of prevention sciences can refer to the Handbook of the EUPC[5] and to the UNODC standards of substance use prevention[6].

- Readers with a concern or question about a specific statement can contact president@euspr.org and request specific literature references for the statements made.

[1] https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/drug-prevention-and-treatment/publications.html

[2] https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/best-practice/xchange

[3] http://www.stad.org/en/about-stad#:~:text=STAD%20(Stockholm%20prevents%20alcohol%20and,of%20alcohol%20and%20drug%20abuse

[4] https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/technical-reports/drug-prevention-exploring-systems-perspective_en

[5] https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/manuals/european-prevention-curriculum_en

[6] https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/prevention/prevention-standards.html