Online Training Instruments for Busy Prevention Workers

Virtual Training for Prevention Workers – Frontline Politeia Paper on Online Training Guidelines

Purpose: To provide a basic conceptual framework and guidelines for online training and encourage trainers and implementers to use it.

Audience: Trainers and implementers of the Frontline Politeia Project

Contents:

- What do we mean by online training

- Why is online training useful?

- How does it work?

- Advantages and challenges of online training for prevention workers

- Virtual Communities of Practice (VCP): key factors for prevention workers’ professional development

- Recommendations for the delivery of an online course

What do we mean by online training?

Online training provides access to learning and acquisition of competencies (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) without having to be onsite in a specific place and mostly without time constraints.

According to Mustari et al. (2021), online learning can be defined as a form of distance education in which material delivery is carried out via the Internet synchronously or asynchronously. Online-, e-, virtual-, computer-mediated-, open-, web-learning, and other related terms are part of a “semantic jungle” (García Aretio, 2020). The diversity of conceptual perspectives about Digital Education territories is due to recent, diverse, unstable, and diffuse foundations (Aires, 2016; García Aretio, 2020).

In the scope of the Frontline Politea Project, we define Online Training within the Digital Education territories as a mediated educational dialogue between trainers and trainees who can learn independently or in groups without geographical barriers or time constraints. According to García Aretio (2020: 10), this definition integrates other concepts such as educating via digital support (using digital technologies), “… dialogue (educational communication and interaction), didactic (pedagogical vision of the acquisition of valuable learning) and mediated (necessary technological component when there is a physical separation between trainers and trainees during the educational process).”

Although online training requires the integration of technology, it is pedagogy that is critical to the success of an online course.

Why is online training useful?

- Several studies (Paul & Jefferson, 2019; Garcia Aretio, 2010; Means et al., 2009) confirm the effectiveness of online training for developing competencies in life-long learning.

- Adopting teaching and learning practices in digital environments has been widely embraced to overcome the limitations of in-presence sessions.

- One of the aims of online training is to reach a wider audience and facilitate access to that training for participants who may not otherwise be able to access that training.

- In some cases, it helps to complement face-to-face learning, contributing to delving further into a subject knowledge and developing certain skills and competencies.

- In other cases, it is the sole methodology for delivering a course and the teaching-learning process.

- It contributes to the digital inclusion of trainees and to reducing costs. It can be less time-consuming if the course can be undertaken from the person’s home or work setting, without having to go to a different place for the training.

Online training will help to empower the prevention work force through innovative learning tools, which they can use at home or at their workplace, thus saving time, if the course is well planned and based on a solid pedagogical framework.

How it works

For an online course to be effective, it needs to (Csirke & Složil, 2022):

- be well-organized into learning units or modules,

- have clear learning goals, objectives and learning outcomes,

- include activities that directly support the learning goals and objectives,

- develop formative and summative assessment activities allowing scaffolding – e.g. TALOE (https://taloetool.up.pt/) or other technological tools

- engage the learner through interaction with content, supporting them in exploring, discussing, and analyzing abstract concepts in real-world, relevant contexts,

- offer rich and relevant resources for students,

- engage the learner in further study and professional development through communication with other students and the tutor after completing the course by offering them tutor support and peer learning in an online

This last recommendation can be achieved by creating a Virtual Community of Practice (VCP), one of the objectives of the Frontline Politeia project (see below).

Advantages and challenges of online training for prevention workers

Online training has many advantages but poses some challenges that must be addressed. We include some of the most significant ones in this section, although there can be many others, depending on the specific needs and situations of the participants.

Among the advantages, we can highlight the following:

- Flexibility – training can be done anywhere and anytime depending on the availability of internet connection and digital devices (personal computer, tablet, mobile phone), and each trainee can follow their rhythm.

- Inclusive – as long as the person has the devices and proper

- Work-related training and workplace

- Methodological

- Collaboration with trainees who live far away from each Creation of networks.

- Sense of Participatory with Autonomy. Digital and media literacy.

- It provides opportunities to some participants who otherwise would not be able to engage in this specific training.

Regarding some of its challenges:

- Online learning requires autonomy, high commitment, and certain digital competence at different levels, depending on the platform used.

- Ensuring collaboration and cooperation is difficult when trainees have not met previously (and sometimes even if they have).

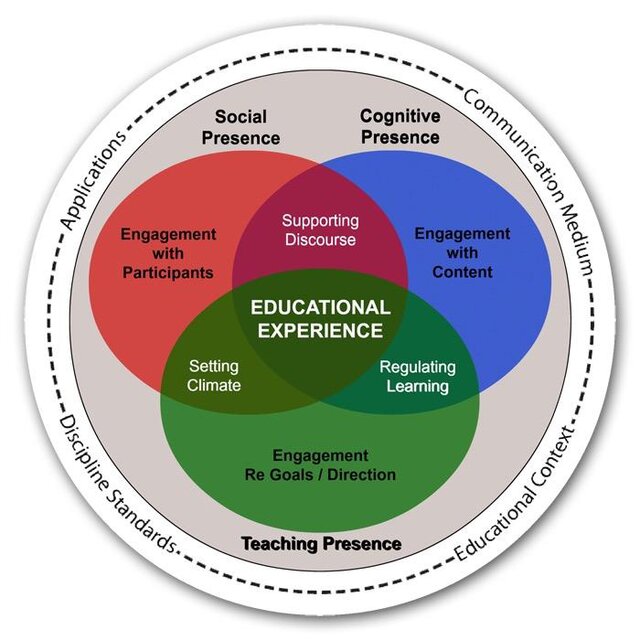

- Social, Teaching and Cognitive dimensions must also be considered (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000).

- Online training requires more concentration and attention from the participants. Hence, e-learning should be shorter in duration than onsite.

- Another challenge is to match the amount of information with the training aims. There must be a good balance in the information load.

- Some people point out that online training is time-consuming. Nevertheless, the argument that live training can also be time-intensive, refutes this challenge. It depends on the workload and time management.

- Achieving interaction and fluent group dynamics online can be challenging, but it is possible. The following checklist is an example of a self-assessment form used in an online course with a compulsory group. It can be used at the beginning of the activity so that participants know what is expected from them about group interaction, and at the end, to evaluate it (further items could be included):

| Group | Frequency | ||||

| Observed aspects | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always |

| 1. Communication among group members flows regularly | |||||

| 2. There is a common interest in exploring issues or topics raised | |||||

| 3. The knowledge /experience of each member is considered | |||||

| 4. Discrepancies and differences are dealt with | |||||

| 5. Tasks distribution is done in a balanced way | |||||

| 6. Each student assumes their responsibility | |||||

| 7. Time is managed effectively to deliver the tasks on time. | |||||

| 8. The contributions by each participant are registered in the forum | |||||

| 9. Students support each other to achieve the group’s goals | |||||

| 10. Students’ different work rhythms and styles are taken into account and managed adequately | |||||

Group work self-assessment (Malik B., Mamolar P., & Senra, M. (2014) Social Justice and Education-UNED (based on the observation scale to assess group work interactions by Izquierdo M. & Iborra A. (2010)].

The key challenge of online training is to create an online learning environment where students do not need to rely on face-to-face contact to learn new knowledge and develop their skills (Csirke & Složil, 2022, p. 4).

Virtual Communities of Practice: key factors for prevention workers’ professional development

Virtual communities can be of practice, when members share good practices and problem-solving strategies; of education, when members are engaged in informal processes of collective learning underpinned by sharing knowledge; and they can also be virtual communities of research when members are involved in knowledge building processes (Henriques, van Hout, Teixeira, 2020).

The concept of Virtual Community of Practice (VCP) refers to a social network of individuals who connect through specific social media, potentially crossing geographical and political boundaries to pursue mutual interests or goals (Wenger-Trayner, et al., 2014).

According to Wenger-Trayner et al. (2014) each virtual community of practice has three key factors that members must address: i) Domain (membership implies a commitment and shared competencies that distinguish members from others); ii) Community (members’ pursuit of shared interest in their domain, engage in joint activities and discussion, help each other, develop relationships which enables learning and share information, support isolated working); iii) Practice (members develop over time and sustainable interactions and a shared repertoire of resources, such as experiences, stories, tools, practices).

VCP requires the action of a leader to generate dynamic and interactive communication processes. There are different roles of the trainer as a facilitator and a trainee as active in their training process. The leaders’ role can change or weaken, depending on how successfully the three major dimensions that come into play in education interact in virtual settings so that they can function as communities of practice and inquiry: the teaching, cognitive and social dimensions (Garrison et al., 2000, Ballesteros et al., 2019) – as we can see in Figure 1:

Figure 1. A visual depiction of the Community of Inquiry Model from http://www.thecommunityofinquiry.org/coi and reproduced under Creative Commons license (CC-BY-SA)

Recommendations for the delivery of an online course

- Explore previous expectations and needs of the

- Build trust among participants considering the diversity of profiles and

- Strengthen trust in digital training environments among trainees and

- Develop ongoing interaction and collaborative culture through different virtual channels in formal and informal settings, even after the training.

- Achieve a balance between the demands and the feasibility of online training, catering to trainees’ needs and expectations and training aims.

- Promote participatory evaluation: peer-evaluation, self-evaluation, …

- Design e-activities that build up knowledge from trainees’ previous background and Experience.

- Use diverse pedagogical methodologies and strategies to improve the learning experience – e.g. gamification, storytelling, Problem-Based Learning (PBL), Team-Based Learning (TBL), building mind maps, e-portfolios, etc.

- Use diverse digital technologies to improve the learning experience – e.g. Padlet, Mentimeter, Tricider, Wordwall, Videoant, Canvas, Genialy, etc.

Specific recommendations to consider once the course has started:

- As a trainer, make yourself present throughout the learning

- At the beginning of the course, publish a message in the forum where our philosophy/ objectives are clear (build trust, encourage communication-based on diversity, create a learning community…).

- Post a message on the platform with practical instructions and explicit rules to participate in the forum (in each message only write about one idea; don’t make the messages too long…).

- Hold one video class/webinar (synchronous) per month to convey closeness between facilitators and participants on topics relevant to the discussion.

- Create spaces or activities where participants can communicate (through the forum, proposed activities, video classes, etc.).

- Promote a feedback culture: timely, frequent, and individualized

- Promote a participatory and collective evaluation, in which participants are the ones who evaluate the work of their peers. An evaluation rubric with criteria should be provided, and course facilitators should guide the process.

- Generate collaborative activities: Design an activity where students work collaboratively (in groups of 2-3 people) to encourage networking among participants. The group work self-assessment scale can be handy as an initial tool so that participants know the criteria they should apply beforehand and as a final evaluation of the group interaction.

- To generate a communication channel so that after the course, participants remain in contact (e.g. Telegram, WhatsApp…).

- To facilitate cross-cultural verbal communication, the following suggestions should be considered (Rocha Trindade, 2003):

- Keep language simple and

- Use consistent

- Reduce or avoid jargon, idioms and acronyms (or explain them if their use is necessary).

- Define terms and provide glossaries (or construct them with participants).

- Use relevant, specific examples familiar to the trainees and encourage them to share their experiences.

- Explain concepts using multiple examples to reduce

And as a final and general recommendation: Enjoy the course and the interaction with participants! Teaching and learning online can be very challenging and demanding, but it can also be fun and beneficial. It is a perfect opportunity for mutual understanding and contributes to laying the foundations of a virtual community of practice, education, and research.

References

Aguado, T., Álvarez, B., Mavridis, L. N. & Browne, A. (2002). Virtual Learning Environments from a Cross-Cultural Perspective (. In M. Barajas (Ed). Virtual Learning Environments in Higher Education: A European View. Publications. Universidad de Barcelona.

Aires, L. (2016). E-Learning, Online Education and Open Education: a theoretical approach. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 19(1), pp. 253-269. http://dx.doi/10.5944/ried.19.1.14356

Ballesteros, B.; Gil-Jaurena, I., Morentin, J. (2019). Validación de la versión en castellano del cuestionario ‘Community of Inquiry’, Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 19(59). http://doi.org/10.6018/red/59/04

Barajas, M. (Ed.) (2002). Virtual Learning Environments in Higher Education: A European View. Publications. Universidad de Barcelona.

Bhoyrub, J., Hurley, J., Neilson, G. R., Ramsey, M. & Smith, M. (2014). Heutagogy: an alternative practice-based learning approach. Nurse Education in Practice, 10(6), 322-GUIDELINES

Csirke, A & Složil, J. (Eds.) (2022) Guidelines on Online Course Development: From Defining the Course Goals and Learning Outcomes to Designing the Course Concept. Erasmus+ Programme, Project N° 2020-1-CZ01-KA204-078378

García Aretio, L. (2020). Bosque semántico: ¿educación/enseñanza/aprendizaje a distancia, virtual, en línea, digital, eLearning…? RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 23(1), pp. 09-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/ried.23.1.25495

García Aretio, L. (2010). ¿Se sigue dudando de la educación a distancia? Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 21(2), 240-250.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., Archer, W. (2000). Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education, The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2- 3), 87-105 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Goldie, J. G. S. (2016). Connectivism: A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Medical Teacher, 38(10), 1064-1069. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173661

González-Sanmamed, M., Sangrà, A., Souto-Seijo, A., & Estévez, I. (2020). Learning ecologies in the digital era: challenges for higher education. Publicaciones, 50(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.30827/publicaciones.v50i1.15671

Henriques, S., Van Hout, M.C. & Teixeira, A. (2020). Virtual ‘Experiential Expert’ Communities of Practice in Sharing Evidence-Based Prevention of Novel Psychoactive Substance (NPS) Use the Portuguese Experience. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00376-z

Jonassen, D. (1999). Designing Constructivist Learning Environments. In Reigelut, C. (Org.). Instructional-Design Theories and Models: A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory, 215-239, Pensilvânia: Pennsylvania State University, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Means, B; Yukie, T.; Murphy, R. Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning. A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies,

U.S. Department of Education.

Mustari, N., Herman, Aris, M., Mawardi, A., & Chaminra, T. (2021). The Effect of Online Learning Policy in the Era of Covid-19 on Students’ Quality. Asian Political Science Review, 5(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.14456/apsr.2021.3

Paul, J., & Jefferson, F. (2019). A Comparative Analysis of Student Performance in an Online vs. Face-to-Face Environmental Science Course From 2009 to 2016. Frontiers in Computer Science, 1, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2019.00007

Rocha Trindade, A. (2003): The Transformation of Higher Education: Convergence of Distance and Presence Learning Paradigms. In M. Barajas (Ed). Virtual Learning Environments in Higher Education: A European View. Publicacions. Universidad de Barcelona.

Wenger-Trayner, E., O’Creevy, M. F., Hutchinson, S., Kubiak, C., & Wenger, B. (2014). Learning in landscapes of practice. Routledge